Porter

When I set out to photograph a porter's journey, I thought I knew just what I was after: one of those grizzled old men I always met on the trail as a Peace Corps volunteer, head bent under a carrying strap until only the slits of his eyes were visible, laboring beneath 40 kilos of rice, smelling of days old sweat, craggy face covered in grime, a shaggy homespun vest hanging in tatters about his shoulders, legs muscled like the cables of a suspension bridge. His feet would have skin a quarter-inch thick, cracked and fissured as a glacier, big toes splayed out at right angles, and each foot flat and wide as a shovelhead.

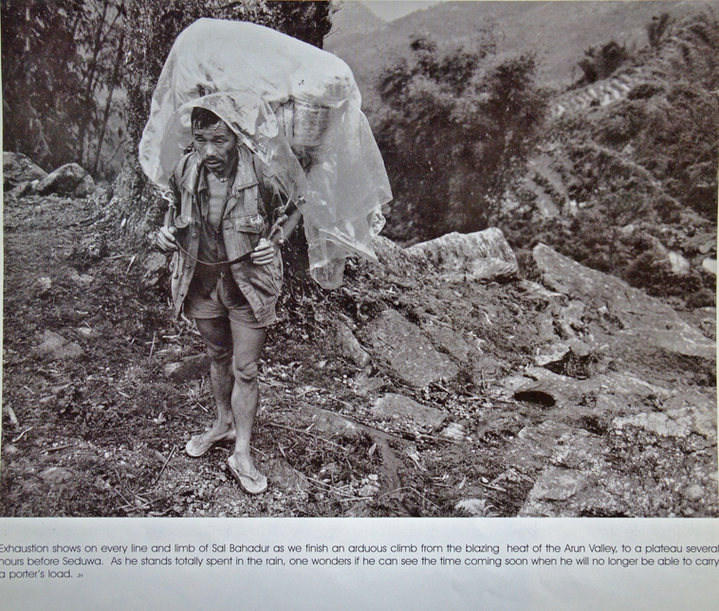

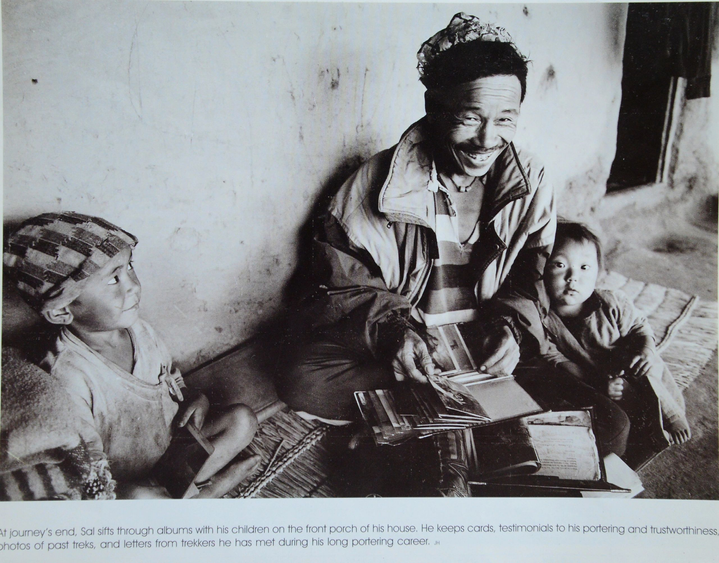

That was my image of a traditional porter, but circumstances led me to Sal Bahadur Rai, 5 feet, 95 pounds, 40 years old and wearing an " Eat at Zelda's t-shirt, dirty jogging pants with yellow racing stripes, a haircut better than my own, and a broken western phrase for every occasion. Sal sits somewhere between my old image and the future. He is a self-taught reader and knows about the outside world, but Nepali society and his second grade education offer him few opportunities to match his hopes. Sal scrapes out a meager living as a porter and rice farmer. His life is neither total misery nor pure joy and ease; it is both and everything in between. It is a life in Nepal and that is what I want to show.

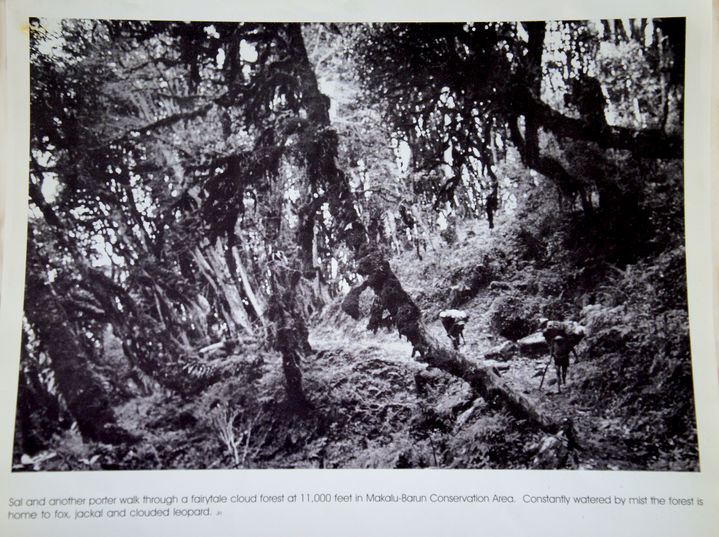

After three weeks of walking next to Sal in the Makalu Barun conservation area of Eastern Nepal, I realized it doesn't matter what clothes he wears. He still shoulders a load almost as heavy as he is, still works for 5 rupees a kilo, and still drips sweat onto the trails that climb up and down the hills of Nepal. I hope my photos amply introduce you to Sal Bahadur Rai.

Some 20 years later I hear that the trade of porter, an intrinsic part of Nepal and village life for centuries that has brought supplies to remote places and employment to young men, is dying out. Perhaps fewer men want to do it, it is physically demanding and one is away from one's family for days on end; but also because the nepal government has been building roads at a breakneck pace, and though prone to landslides and monsoon mud, they have supplanted the job of the porter carrying his doko of goods on his bent back.

Instead of men like Sal Bahadur, a line of noisy, smoking belching, trucks driven mainly by Indians roars into town, loaded with what would take 50 porters to carry, and bringing the universal sounds of a roaring engine, breaking the profound silence of a Himalayan village.